David Allen’s magnum opus on personal productivity, Getting Things Done, is packed with useful insights. Here’s one of my favorites:

The smart part of us sets up things for us to do that the not-so-smart part responds to almost automatically, creating behavior that produces high-performing results. We trick ourselves into doing what we ought to be doing.

He then offers this classic example: putting something you need to take with you near your car keys. My personal crutch in this department is alarms. Even if my future action needs to be done a mere ten minutes from the present moment, it’s likely I’ll blow it unless I set an alarm.

I’m guessing all of us have used these kinds of tricks, even if we hadn’t considered it from the perspective above.

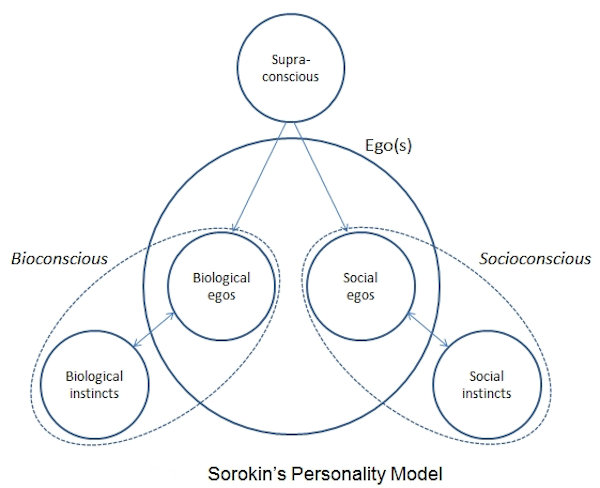

The most basic component – that there are multiple ‘parts’ or ‘selves’ living inside us – runs counter to the socially agreed experience of one self with the conveniently rememberable label, ‘Chad’, somehow assigned to this one body I wake up in every day. And I do appreciate the convenience of that definition – it certainly makes it easier to carry on a conversation with friends.

Behind the scenes, though, lurks a small theater’s worth of ‘sub-personalities’ – distinct packages of ego that carry their own thought patterns, fears, and desires. Ever felt like you wanted to do something, and didn’t want to do it at the same time? Ever watched two parts of yourself duke it out for control in a situation? Lord knows I have, many times.

Particular to Allen’s productivity trick above is the distinction that different parts of ourselves have different capacities. The part of me that sets alarms knows that most other parts of me are clueless about when something should be done. It is wisely anticipating the future stress, disappointment, and guilt from hogging my town’s community EV charging spot long after my car is fully charged.

I’ve noticed this variance in capacity along other dynamics, too. My move across the country to homestead offers a clear example: a courageous and wise part of me calculated how to get the scared parts of me to run in the right direction when I got here – a feat it accomplished by constructing barriers that sealed off escape routes from my commitment.

I could have rented out my condo in Portland, Oregon, giving me the option to easily return – I’d done that in 2013 when I briefly moved to Austin, Texas. Instead, I sold my place. I also could have held my plan closer to the vest, only revealing it to a few trusted people, and made it easier to bow out. I sure as hell didn’t do that! Instead, I’ve made the most public commitment to a project in my entire life.

Believe me, the scared parts have come online since I got here. “This is overwhelming.” “What the hell am I doing here?” “The world feels big, and I feel really, really small.” And like bumpers on a bowling alley, the choices above shaped the path forward in one sensible direction: towards the goal. No home in Portland gave me nowhere easy to return to. A public commitment to the project fired up the value of keeping my word.

Instead of repressing feelings and needs, I use this tactic to guide those less aware parts of myself into behaviors that are, let’s say, more productive – as a parent would outsmart their child for mutual benefit: “would you like to choose this thing that works for me, or this other thing that also works for me?”

When the scared parts of me run toward a goal, they get a little medicine every time. It’s not as scary as it seems, and everything’s going to be OK.